Rishi Siddhaantas and Manuja Siddhaantas

The thousand years before Aryabhata were as

rich in intellectual fervour and activity as the thousand years after him. This

was the era of the composition of most of the Vedaangas, the creation of such seminal works like Bharata’s NaatyaShaastra, Chanakya’s ArthaShaastra, Vatsyayana’s KaamaSutra, and several magnificent

treatises on various subjects. Among these were eighteen jyotisha siddhantas,

all attributed to deva-s like Surya or rishi-s like Kashyapa, Atri, Mareechi as

described in this sloka.

सूर्यः पितामहो व्यासो वसिष्ठोऽत्रि पराशरः ।

कश्यपो नारदो गर्गो मरीचिर्मनुरङ्गिराः।।

लोमशः पौलिशश्चैव च्यवनो यवनो भृगुः ।

शौनकोऽष्टादशश्चैते ज्योतिःशास्त्र प्रवर्तकः ।।

Surya

pitaamaho vyaaso vashishto atri paraasharaH

Kashyapo

naarado gargo mareechi-r manu-r angiraaH

lomashaH

paulisha-shcaiva chyavano yavano bhrguH

shaunako

ashtadasha-shchaite jyoti shaastra pravartakaH

This stands in stark contrast with the

Siddhantas in the post-Aryabhata classical era, all of which are ascribed to

scholarly astronomers, but not rishis. Varahamihira’s phrase manuja-grantham, succinctly describes this.

This was the period during which numerals,

the place value system, angular units like degrees, minutes and seconds,

trigonometry, and several such mathematical concepts must have been discovered.

Instruments like shanku (gnomon), chakra (hoop), gola (armillary sphere),

ghati yantra (copper pot) were used.

But all 18 siddhantas are now lost, except the Surya Siddhanta, which was modified and updated in the later centuries. Fortunately, Varahamihira, a contemporary of Aryabhata, wrote a treatise called Pancha Siddhantika, a comparative study of five of these eighteen siddhantas. He quoted and explained several verses from them. So, we understand some concepts of the era.

Types

of Jyotisha texts

Jyotisha texts come in several categories. Siddanta-s are once in a century grand

texts, composed by superlative scholars. A siddhanta may have several

commentaries, called bhashya-s, in

the succeeding centuries. For practical use, more compact books called karana-s were composed, which was used

by pandits to prepare almanacs/calendars called panchaanga-s for public use. The latter tradition is still extant.

It is my belief that the various texts on

astronomy and mathematics rival the commentaries and compositions on the

Ramayana and Mahabharata. So rich and so widespread was the literature.

Pancha

Siddhantika

The five siddhantas Varahamihira studied,

those of Pitamaha (Brahma), Vashishta,

Surya, Romaka and Paulisha,

explain motions of planets (in a geocentric model), prediction of eclipses,

sine tables, celestial longitudes and latitudes. None of these are mentioned in

Vedanga Jyotisha. They vary mostly in minor details, which Varahamihira

explains. The small Vedic yuga of five years was dropped, and the humongous

yuga of 432000 years used. We have no idea when or how this changed. A day

count, ahargana, counting number of solar

days (regardless of month or year) since the start of the Kaliyuga, which began

when the Mahabharata war ended, came into vogue. Kaliyuga years are found

inscribed in several royal inscriptions; for example, the Anamalai inscription

of Maranjadayan Varaguna Pandyan in Madurai.

The solar zodiac is used extensively. It was

most probably borrowed from the Greeks or Babylonians. The solar zodiac is a

popualar theme on ceiling sculptures of temples in Tamilnadu, like this one in

Kudumiyan Malai, Pudukottai.

Romaka (also called Lomasha) and Yavana

refer to a Roman and a Greek, Paulisha to a Paulus Alexandrinus, say historians

of science. While some foreign ideas were obviously borrowed, there is a

puzzling absence of inclusion of other ideas, including those of Euclid,

Ptolemy, or Archimedes. Whereas the Greeks developed an epicyclic theory of

planetary motion, Indians developed a theory based on air strings pulling the

planets. Geometrically, these are simply different epicyclic model than those

used by the Greeks. They involved extremely complicated geometry, trigonometry

and algebra, but they were quite accurate in predicting eclipses, solar and

lunar, the biggest challenges of Indian astronomy.

That Mercury and Venus had a different type

of orbital movement, from the other planets, Mars Jupiter and Saturn, was

realized. Siddhantas explain eight types of planetary movement.

A vocabulary of scientific and technical

words developed, to describe both such astronomical concepts and mathematical

ideas and theorems.

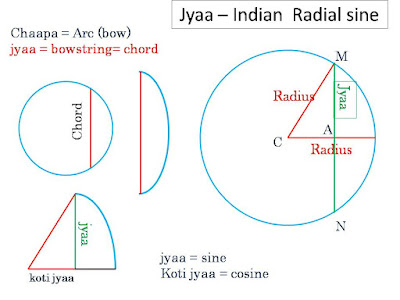

From the earlier knowledge of hypotenuses

and circles, as found in Sulba Sutras, we can understand that the concepts of

sine, cosine and other trigonometric ideas arose. The Indian sine was not the

opposite/hypotenuse that we learn in school today, but the radial sine

(abbreviated as R-sine), called the ardha-jyaa

(half-bowstring). A chord connecting the ends of an arc looks like a bow

(Sanskrit: chaapa or dhanush). When seen as part of a circle,

the radius of the circle (CM )is the hypotenuse of the triangle (CMA) formed by

the half-chord (MA), the radius touching the top (M) of this chord, and the

segment (CA) of the radius dividing the chord into two equal halves. In Indian

siddhantas, in the table of sines, expressed as a series, only the numerators

are listed. Hence they are radial sines (multiplied by radius). The word for

cosine is koti-jyaa.

The word jyaa and this concept of trigonometry traveled from India to

Baghdad in the eighth century during the reign of Caliph al-Mamun, along with

the zero, the decimal place value system, Indian numerals (now called Arabic

numerals) and the works of Aryabhata and Brahmagupta. It transformed into the

Arabic word jyaab or jeyb which means pocket. This then was

taken to Europe by Leonardo Fibonacci, an Italian merchant, in the twelfth

century, and translated into Latin as sinus, and later into English as sine.

Then it came to India under English colonialism, making a full circle (pardon

the pun) into our mathematical textbooks as sine. We learn trigonometry as the

gift of the Europeans, not realizing its Indian origin.

Angular measurements called kalaa (degrees) liptaa (minutes) and viliptaa (seconds), were used, based on the sexagesimal system (Base-60) rather than

decimal, which hints at a Babylonian origin. In addition, a sub division of the

second into sixty parts and division of the cirlce into twelve parts (called raashi) also existed. Angles were often

represented in karana texts with five aspects, not just the three we use today.

The division of time was also sexagesimal,

with a day consisting of sixty naadis,

each naadi of sixty vinaadis.

Remember, the naadi existed in the Vedic period; was it indigienous or

imported? It’s not one of several mysteries.

Step by step mathematical procedures (now

called algorithms, after the Uzbek mathematician,

Mohammad ibn Musa al-Khwarezmi) also emerged in the era of 18 Siddhantas. The

place value system and zero were invaluable in developing algorithms for

multiplication and division, square and cube roots, and several algebraic

procedures solving indeterminate linear equations.

Ujjain

Meridian

Two millennia before the world adopted the

Greenwich meridian, Indian astronomers used the Ujjain meridian, as the prime

meridian of longitude in India. This is the longitude that passed from north

pole (Meru) to south pole (Vadavamukha). That the earth was a globe, not a flat

plain was well understood by astronomers. They believed that Devas lived at

Meru and Asuras at Vadavamukha, and Mankind in between.

गगनमुपैति शिखिशिखा क्षिप्तमपि क्षितिमुपैति गुरु किञ्चित् ।

यद्वदिह मानवानामसुराणां तद्वदेवाधः ॥ १३– ४ ॥ Pancha Siddhantika 13-4

Gaganam-upaiti

shikhi-shikaa kshiptam-api kshitim-upaiti guru kincit

Yadvad-iha

maanavaanaam-asuraaNaam tadvadeva-adaH

The flame (shikhaa) of a lamp(shikhi) points skywards (gaganam) and a heavy (guru) object (kincit) thrown (kshiptam) skywards falls back to earth (kshiti); this happens in the lands of men (maanavaanaam) and asuras (asuraaNaam)

This was one concept of gravity, before Newton changed it.

उदयो यो लङ्कायां सोऽस्तमयः सवितुरेव सिद्धपुरे ।

मध्याह्नो यमकोट्यां रोमक विषयेऽर्धरात्रं स॥

Pancha Siddhantika 15-23

Udayo

yo lankaayaam sa-astamaya savitur-eva siddhapure

Madhyaahno

yamakotyaam romaka-vishaye arddha-raatram saH

Translation When it is Sunrise (udaya) in Lanka, it is Sunset (astamaya) in Siddhapura, Noon (madhyaahna) at Yamakoti, Midnight (arddha-raatra) in Romaka-vishaya

Lanka is not the Sri Lanka we know, but the point where the Ujjain meridian intersects the equator. Ujjain was a major center of learning in ancient India, and is also perhaps closes to the Tropic of Cancer (Karkata). We don’t know what places Yamakoti and Siddhapura signify, perhaps they are also place marker names like the equatorial Lanka.

While all the other Siddhantas determine time with Ujjain as the prime meridian, Romaka Siddhanta says the days starts with sunset at Yavanapura, which is not Athens or Rome, but Alexandria in Egypt.

The logical thought process which inspired the use of Ujjain and Lanka for calculations is simple, but brilliant. Longitude and latitude determine local time. So, the times of sunrise, sunset, moonrise, eclipses, will vary from place to place. Once the calculations are made for a prime meridian like Ujjain, local panchaangam-s can be prepared with only minor changes applied for local longitude and latitude – these are called deshantara, Each Siddhanta has a section about it.

Celestial longitudes and latitudes were

easier to calculate, than those on earth. The Surya Siddhanta lists Rohitaka

(Rohtak, Haryana) and Kurukshetra and other cities on the Ujjain meridian.

Others list such places as Kanyakumari, Malavanagar, Sthaneshvar, Vatsyagulma,

Mahishmati, Vananagara as cities on the Ujjain meridian.

Some

trivia : Ujjain passed on its torch to Madras, briefly. Today, Indian

standard time is set on longitude 82.5E,

based on Greenwich meridian. But for about a century, the Madras

meridian was used as the prime meridian, especially for railway clocks.

For the entire series click this link --> Indian Astronomy and Mathematics

References

1.

Surya Siddhanta, by

Phanindralal Gangooly

2.

Pancha Siddhantika, edited by

KV Sarma

3.

Pancha Siddhantika, edited by G

Thibaut, Sudhakara Dwivedi